In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the scale of investment required to address global health and environmental issues. Action on funding for global health include renewed commitments to the 1970 target for official development assistance of 0.7 per cent of GDP/GNI, and the development of new instruments for financial and other forms of assistance. In general, these instruments recognize that health is a global concern affecting rich and poor countries, and that it represents an economic investment in future productivity as well as a humanitarian issue.

As such, instruments seek immediate sources of investment to address these long term issues. These include the Airline Solidarity Tax, the International Finance Facility for Immunisation, Advanced Market Commitments, MDG Contracts and IDA Buy Downs.

The discussion of financing for global health is usually dominated by a debate on funding for development and a call to donor countries to increase their support of – and make good on – commitments to developing countries. Lately, an additional debate on financing global public goods – such as global disease surveillance systems – has emerged, and UNDP is suggesting a new approach to global public finance. The neglected area of financing for global health is the financing of the regular budget of international organizations, such as WHO. There is a tendency to fund diseases, issues and programmes – as discussed below – but not governance structures. However, this has led to a significant weakening of a number of international organizations. Europe should be at the forefront of exploring new financing and governance mechanisms that ensure all three strategic priorities of global health: security, equity and good governance.

The most comprehensive study on resource needs for global health remains the report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (CMH), which was commissioned by WHO and directed by Jeffrey Sachs, while other estimates tend to focus on the resource needs for single issues or diseases. The CMH report starts with the observation that “only a handful of diseases and conditions are responsible for most of the world’s health deficit: HIV and AIDS; malaria; TB; diseases that kill mothers and their infants; tobacco-related illness; and childhood diseases”. In order to improve health in the developing world, additional financing, especially in three areas, is required: the scaling-up of existing interventions, research and development, and global public goods.

The report states that effective interventions exist to prevent or cure most of the above-mentioned diseases. Both national and international spending, however, is insufficient to meet the challenges. While total spending on health per person per year amounts to nearly US$ 2,000 in rich countries, it is only US$ 11 in the least developed countries (with US$ 6 being public domestic spending, US$ 2.3 being donor assistance and the rest being out-of-pocket expenditure). In order to scale up the existing interventions and to prevent 8 million of the 16 million deaths per year from the above-mentioned diseases, spending of US$ 34 per person per year would be necessary. The CMH report therefore recommends that the developing countries should increase their budgetary spending on health by an additional 1 per cent of GNP by 2007 and 2 per cent by 2015; for their part, donor countries should help to close the gap by increasing spending from the current levels of health-related ODA of approximately US$ 6 billion per year to US$ 27 billion by 2007 and US$ 38 billion by 2015.

More recent studies do not focus exclusively on health but deal instead with the resource needs for the entire process of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The study of the High-Level Panel on Financing for Development, which served as input for the 2002 International Conference on Financing for Development, was the first to specify the amount of ODA required to meet the MDGs. The study gives the often cited figure of US$ 50 billion per year, supplemented by US$ 3 billion per year for humanitarian aid and US$ 15 billion per year for the provision of global public goods, leading to a total of US$ 68 billion per year or a doubling of the current levels of aid. Other studies essentially confirm these figures, while NGOs like Oxfam (2002) assume a global need of around US$ 100 billion per year. The report of the Millennium Project (2005) estimates there source needs to be even higher and states that, in order to achieve the MDGs, ODA of US$ 135 billion per year (equal to 0.44 per cent of GNI) will be needed in 2006, and that international funding will have to rise to US$ 195 billion per year (equal to 0.54 per cent of GNI) by 2015.

This logically leads to the question of where the additional money should come from. The report of the Millennium Project does not say much in this respect; it only vaguely mentions the option to ‘frontload’ ODA through capital markets via the International Finance Facility (IFF), as proposed by the then UK finance minister, Gordon Brown. Other studies go further on these issues and list other options like global taxes, for example, on currency transactions, carbon emissions, airline tickets, weapons sales or the profits of transnational corporations (TNCs), voluntary contributions (for example, a global lottery, donations) or further debt relief. They state that these possible financing mechanisms should be in addition to existing financing – and point to the danger of a crowding out of traditional ODA spending on health. They also claim it is necessary to balance between conditionality, on the one hand, and the need for sustainable and predictable financial flows on the other; and that issues of donor harmonization, governance and the participation of Southern actors should be addressed, and that possible new mechanisms should be discussed in the context of debt relief and trade reform.

A number of key issues are beginning to emerge, which bring into question some of the financing mechanism issues raised above; they would need to be part of an intensive discussion at European level and are, therefore, mentioned only in passing. They include the following:

- the effectiveness of the foreign aid mechanism

- the balance between funding development in health and global public goods for health, such as global disease surveillance systems

- the need to fund good global governance infrastructures

- the problematic approach to programme funding, which can reduce investments in health systems

- the importance of direct private investments in countries as opposed to foreign aid

- the role of debt relief in freeing up resources to support health within a country

- the opening up of European markets, such as in agriculture, to allow poor countries to compete

In September 2008, a High Level Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems was established to address some of these questions.

More on New Funding Tools

Further Definitions

Airline Solidarity Tax:

The idea for a tax to be levied on international flights and the revenue used for scaling up funding for the Millennium Development Goals was first put forward by a working group commissioned by Former French President Jacque Chirac in 2004. Discussed among other tools, the Commission report proposed international taxation as a tool to ensure stable and continuous contributions and a way to redistribute the wealth created by globalization to the fight against poverty and inequality. At the UN Millennium +5 Summit in September 2005, the “Lula group” persuaded 66 countries to support a proposal for an experimental tax at the international level and to sign the “Declaration on Innovative Sources of Financing for Development”. The European Commission also released a staff working paper that analyses how a contribution on airline tickets might be used by EU Member States as a source of development aid. As a result of these efforts it was eventually decided to pilot an international solidarity contribution on plane tickets to finance against HIV/AIDS and other pandemics.

The idea of international air-ticket solidarity has first been implemented by France on the grounds that such an initiative would help make globalisation more equitable. It was launched in February 2006 at the Ministerial Conference on ‘Solidarity and Globalization: Innovative Financing for Development and against Pandemics.’ Shortly thereafter 14 countries (Brazil, Chile, Republic of Congo, Cyprus, France, Ivory Coast, Jordan, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Mauritius, Nicaragua, Norway, Republic of Korea and the United Kingdom) followed suit. Similar to how the IFFIm was established as a sustainable financing tool serving the GAVI Alliance, it was decided that the solidarity tax would be set up to finance UNITAID. UNITAID is an international facility which “aims to improve access to treatments against HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis for the populations of developing countries, by getting lower prices of quality medicines and diagnostics which are still too expensive for these countries, and speed up their availability and delivery in the field.”

The airline tax is essentially a series of national taxes that countries commit to levy voluntarily. Once implemented, the tax is applied to all airlines departing from countries which are imposing it. A levy on airline tickets is paid by passengers when purchasing the tickets as a form of ad-valorem tax. It is often added to existing airport tax. And it up to the country do decide on rates and conditions. For example in France the tax is highly differentiated, with economy class passengers paying maximum rates of EUR €1 per departure to destinations within Europe and EUR €4 to destination outside of Europe. For business- and first-class travellers the rate is higher at EUR €10 and €40 respectively. The revenue is collected by airline companies who act as intermediary agents and forwarded directly to UNITAID, or to national governments which will then further forward revenue to UNITAID as agreed.

Initially opponent to the tax suggested that it would be a distorting force in the market with a potential to disrupt demand; however, since the launch in 2006 there has been no evidence to support this claim. Though it cannot be attributed to the tax, airline carrier Air France actually saw a +5% increase in traffic a year after the tax was instituted. While various points of criticism have been raised, ranging from questions of efficiency to equity of such tax, the tax does appear to be performing with success. Currently 82% of UNITAID funds come from the tax. In 2007 the UNITAID budget exceeded U.S. $320 million and is expected to rise as high as U.S. $500 million in 2009. Furthermore, the tax presents very little extra administrative burden as its collection is embedded in existing structures.

The airline solidarity tax is not the first international tax that has been considered. For a brief time what was known as the Tobin Tax sparked heated debate. This tax was suggested as a means to control dangerous speculation on the foreign currency exchange markets-a goal which many economists determined it could not achieve. The discussions around the Tobin Tax left a stigma on the subject of international taxes. The success of the airline solidarity tax for UNITAID has reopened this debate in a new positive light. European global health actors should consider new ways to implement similar sustainable funding projects.

International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm):

The International Finance Facility is a mechanism designed to front-load the disbursement of expected future increases in ODA, i.e. paying out pledged development aid funds in larger lump sums now instead of in the gradual increases set for disbursement in due course. The funds for this would be raised on capital markets through the issuance of bonds, back by pledges from participating governments, as securitisation, as had already become a common tool of commercial banking. This concept was first mentioned in 2001 and was first developed in the United Kingdom by the International Poverty Reduction Team in HM Treasury in cooperation with Goldman Sachs. In a paper published in 2003, the proposed expectation was that a $400 billion IFF would disburse on average $40 billion per annum for 10 years to address the Millennium Development Goals.

In 2004 it was decided to launch a “test” IFF and the recipient sector would be health. By the Gleneagles G8 summit in 2005 GAVI, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation, was officially chosen as the recipient for the first IFF for Immunisation (IFFIm). While from the on-set, the IFFIm was received as a positive development by most nations, it would be become primarily a tool of European donors. Prominent participants outside of the UK have been France, Italy, Spain, Norway, Sweden, and South Africa. The reason for this is directly related to governance structures. While the US remains an important bilateral donor to GAVI, constitutionally the US government could not make the long-term pledges required. The US Constitution prevents the fiscal binding of future Congresses by requiring the government to go back to congress for every cycle (yearly budget). Similarly, major donors like Australia, Canada and Japan would not participate as the structure of the IFFIm would have required taking all the expected payments through the budget upfront, with no budgetary benefits, unlike just simply giving GAVI funds directly.

Based on assets in the form of irrevocable and legally binding grant payments from participating sovereign government sponsors to be paid over a 20 year period, the IFFIm issues AAA (Fitch/Moody’s/S&P) rated bonds in international capital markets. The funds raised by the IFFIm’s “Vaccine Bonds” are used for health an immunisation programmes through the GAVI Alliance in 67 eligible countries (the 72 poorest countries with the exclusion of Cuba, North Korea, Somalia, Zimbabwe and Sudan). The inaugural bonds were issued in London on 14 November 2006 with a settlement date of 14 November 2011. The bonds were purchased by geographically diverse investors such as central banks, pension funds, fund managers and insurance companies. From the initial $1 billion raised, net proceeds were $995 million. $953 million were disbursed to GAVI and in 2007 $912 million of the funds were spent in 43 countries. The second issuance occurred in the Japanese market on 18 March 2008 and a third is planned for the near future. A second round of programming also achieved $1.49 billion in spending, two thirds of which had already been distributed by June 2008.

In the first few years of this pilot programme several advantages and disadvantages of financing through the IFF have been identified. Firstly, there are the collective benefits of front-loading, which refers to “the changing of the phasing of a programme so that it uses the same total inputs, but uses them more quickly, the aim being to generate greater returns than if the same total inputs were spread over a longer period of time.” Front-loading produces multiple benefits especially in the case of funding vaccines. Vaccines are the most effective way to combat infectious disease as they not only reduce the risk of the vaccinated, but of all those who come into contact with them. Front-loading of funds translates into the front-loading of vaccine supplies. This facilitates large-scale vaccine campaigns which are more effective than slower rates of distribution over time. However, front-loading is not without costs. Borrowing in commercial markets means that interest and transaction costs would be higher than borrowing publicly. DFID has estimated that 3.5% of total expenditure was incurred this way. Second the drastically increased demand brought on by front-loading increases the price of vaccines. The price of vaccines also tends to fall over time signalling potentially high opportunity costs in front-loading when compared to purchasing in normal quantities over time.

A second advantage is that to be successful the IFFIm does not require participation from all donors, that is to say that donor governments are not required to participate, and not at a pre-arranged amount, such as in the case of contributions to the World Bank. In contrast however, conditionality has reappeared as a potential drawback. There is a conditional payment structure in place which means that some of the potentially most needy countries, such as Zimbabwe which at present is experiencing one of the world’s largest recorded Cholera outbreaks-a disease for which an under-used vaccine has been available for decades-are not benefiting from GAVI programs funded in this way. Likewise, there are some restrictions to which donors can participate. This is necessary in order to maintain the AAA ratings of the bonds, but it also means that some donors, such as emerging economies, may not be able to contribute except in moderate amounts.

Whether or not the IFF actually provides additional funding is also questionable. Though additional benefits will be achieved through front-loading vaccines, if donors’ payments are deducted from future aid flows then no additionality of funding will have been achieved.

Yet despite these drawbacks, many lessons have been learned in the development of future IFF programmes, and an initial evaluation carried out by the Brookings Institute and the IESE concluded that few other vehicles could provide such long-term predictable funding.

Advanced Market Commitments (AMC):

The advanced market commitment (AMC, also known as advanced purchase commitments) is one of a number innovative means to finance the supply of vaccines to developing countries. It is a market-based tool, in the form of a binding contract between a private company and donors which “provides a credible commitment by one or a set of donors to purchase a certain quantity of a specified new or improved product at a defined price, if and when it becomes available.” (ODS, 2003) The AMC is considered a tool of the “pull” variety in that it provides incentives for private actors (firms) on the output side of the activity. Generally speaking, this involves using market mechanisms, such as price in the case of patents, to create financial incentives for firms to engage in behaviour which creates positive externalities for society. This can be contrasted with “push” tool which provide incentives on the input side, i.e. interventions which impact costs, for example a government grant for research and development.

Distinct from patents, the most common and widely known variety of pull tools which guarantee market exclusivity to an innovator, the AMC guarantees the existence of a profitable market. The AMC directly addresses the largest barrier to research and development investment in neglected diseases of poor countries-the low ability of individuals, firms and governments to pay. In this way the AMC attracts private investment to fund the development of a vaccine through the entire “pipeline” from discovery and research to early and late development, through to licensure and finally the supply of the product to those who need it. Another interesting characteristic of the AMC is that the funds are not used to reward the innovators of new pharmaceuticals directly, but rather to purchase units of the product. This thereby encourages the diffusion of the innovation.

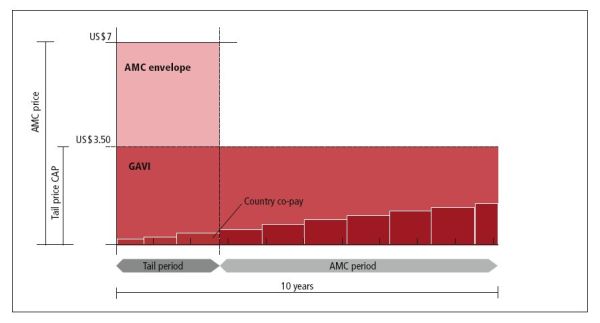

On Feb. 9, 2007, 5 countries (the United Kingdom ($485 million), Italy ($635 million), Norway ($50 million), Canada ($200 million) and Russia ($80 million)), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation ($50 million) committed $1.5 billion to launch the first AMC to help speed the development and availability of a new vaccine for pneumococcal disease which is expected to save the lives of 5.4 million children by 2030. The AMC is expected to become fully operational in early 2009, just 9 years after the concept was first brought forward in academia. In this pilot case of the AMC each manufacturer who chooses to participate makes a binding agreement to supply vaccines for ten years at $3.50 per dose or less. In return, the AMC guarantees a profitable market by subsidising the purchase of the vaccines with the $1.5 billion and with pledged co-financing from the GAVI Alliance (to the limit of a unit price of $7), while also making legally-binding commitments to buy 20%, 15% and 10% of the supply over the period of the AMC. During this time developing country partner co-pays will gradually increase. This is graphically explained in the below chart:

However, the AMC is not without its risks. The proof of the concept will be whether companies respond to the offer. If they do not than no AMC funds will be spent.

MDG Contracts:

The MDG Contract is a new instrument for European development aid. The funds come from the 10th European Development Fund (EDF 10) but they are used specifically for general budget support (GBS) which aims at building the capacity of recipient countries’ governments as well as providing more predictable aid flows. It is part of the Commissions’ response to international commitments to provide more predictable assistance to developing countries

The MDG Contract would have the following key features:

- 6 year commitment of funds for the full 6 years of EDF 10;

- Base component of at least 70% of the total commitment, which will be disbursed subject to there being no unambiguous breach in eligibility conditions for GBS, or in the essential and fundamental elements of cooperation;

- Variable performance component of up to 30%, which would comprise two elements:

- MDG-based tranche: At least 15% of the total commitment would be used specifically to reward performance against MDG-related outcome indicators (results, notably in health, education and water) and public finance management (PFM) reforms following amid-contract review of progress against those indicators. Performance would continue to be monitored annually, but any possible financial adjustment would be deferred to the second half of the programme.

- Annual Performance Tranche: In case of specific and significant concerns about performance with respect to implementation of the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP), performance monitoring (notably data availability), progress with PFM improvements, and macroeconomic stabilisation, up to 15% of the annual allocation could be withheld.

- Eligible countries would be those with GBS programmed under the 10th EDF, that have a successful track record in implementing budget support, show a commitment to monitoring and achieving the MDGs and to improving domestic accountability for budgetary resources, and have active donor coordination mechanisms to support performance review and dialogue.

The Commission expects to proceed (subject to final Member State approval) with MDG-Contracts in 7 countries in 2008 [Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, Mozambique, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia], with Tanzania expected to proceed in 2009. Collectively these would account for 50% of all General Budget Support commitments in EDF 10 national programmes, and some 14% of all EDF 10 national programmes. Coverage may be expanded to other countries (including non ACP ones) as we learn from experience and countries’ monitoring frameworks improve. But alternative approaches will still be needed for countries not yet eligible for budget support. The “MDG Contract” is thus only one important part of the solution towards improving aid effectiveness and accelerating progress towards the MDGs.

IDA Buy-Downs:

The International Development Association (IDA) is the arm of the World Bank Group that provides loans and grants to least developed countries. According to the Bank “An IDA “buy-down” refers to a third party donor paying off all or part of a specific IDA credit on behalf of the government. A country receives an IDA credit to help support specified development activities.” IDA Loans, also referred to as concessional loans or credits, are interest-free loans that offers a much longer grace period and maturity than other forms of financing. The first buy-down was launched in 2003 to help eradicate Polio in Nigeria. The idea is that the IDA supplies a loan to a poor country to purchase the necessary quantity of Polio Vaccinations. Donors then “buy down” a country’s IDA loans upon successful completion of that country’s polio eradication program. To fund the buy-downs, donors established multi-donor trust funds. A US$50 million investment will buy down US$120-140 million in World Bank IDA loans. In this way, developing countries can mobilize what ultimately becomes performance based grant funding to eradicate polio, and thus contribute beyond their national borders to the global campaign to eliminate polio transmission worldwide. Similar to results based financing this tool is based firmly on achieving results and not merely good intentions. The IDA buy-down is currently being considered alongside the IFFIm and the AMC as one of the new innovative sustainable finance tools of high potential.

Currency Transaction Taxes:

The idea of levying a marginal tax on international currency transactions was first promoted by James Tobin the American Nobel prize winner in economics, its primary purpose was to prevent speculators destabilising the foreign exchange system after the US left the gold standard. It was promoted by other international economists as a way of both securing the international currency system and generating substantial aid finance. Various proposals have been put forward for such a tax – from a level of 0.005% to 0.25%, some have suggested that such taxes need to be applied by every country if they are to succeed but more recently it has been accepted that this is not necessary. While global financial transactions amount to some Euro 2 trillion per day only a small proportion involve international currency, about Euro 7 trillion per year. These are nevertheless very large sums thus even a small and partial Currency Transaction Tax could generate large returns both for the country levying the tax and as a global development fund. In recent years the idea of a Currency Transaction Tax has been studied by the UN and promoted by many European leaders. There is now support from France, Belgium, Austria, Germany and most recently the UK. However, the concept has not yet been incorporated in European law or policy and is opposed by the US administration.

Useful Web Sites

- Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health

- Report of the High Level Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems

- France Diplomatie: on UNITAID

- IFFIm Supporting GAVI

- GAVI/Advanced Market Commitments for Vaccines

- MDG Contracts: Brief Description

- MDG Contracts: Further Info

- World Bank News and Broadcast on IDA Buy-Downs

- Global Policy Forum: Currency Transaction Costs